Were There Fewer Concussions in the 2016 Preseason? A Study in Uncertainty and Trends

I almost named this blog “Probably Doubtful” since one of our cardinal reasoning sins as humans is overconfidence. We routinely don’t or improperly consider the uncertainty we have in anything, numbers included. Socrates wasn’t talking about modern statistics when he said “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing,” but we’d all probably lead better lives if we said this to ourselves once a day.

The headline figure is that concussions dropped from 83 in the 2015 preseason to 71 in the 2016 preseason. Let’s dig in a little more deeply and see what we think once we take our uncertainty into account.

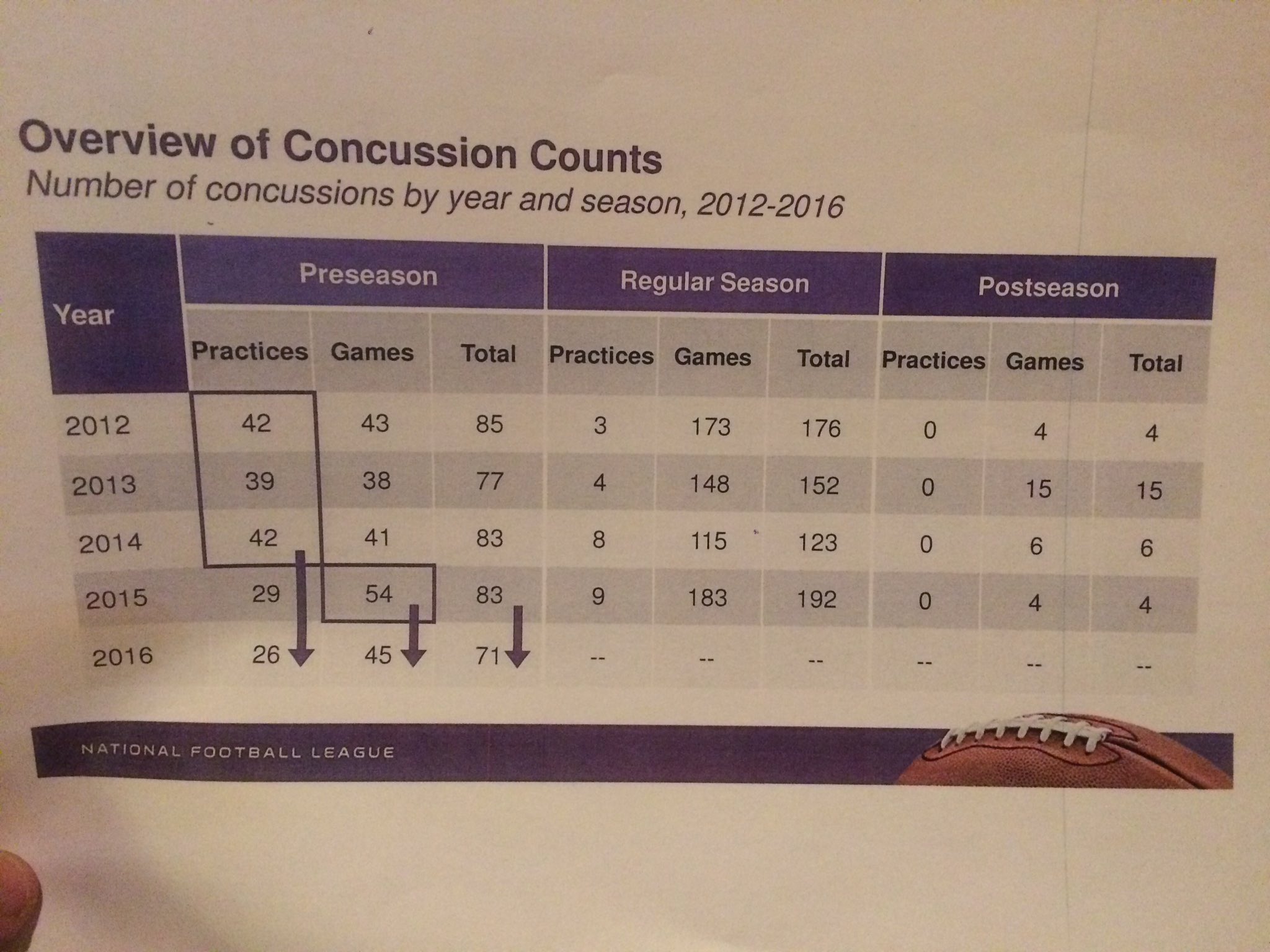

Here are the actual League-reported concussion numbers1 for the 2012-2016 preseason, put together by a company called Quintiles that also tracks the NFL’s other injury data. These numbers break out the regular season and postseason for 2012-2015, too, but let’s just zero in on the preseason numbers for now.

We could approach quantifying our uncertainty in a statistical way or a “non-statistical” way. Let’s ease in by starting with the latter:

“Non-statistical” Approach: Historical Variation

Just look at the numbers, reproduced below:

For overall concussions (games + practices), the 2016 number actually looks pretty good – lower than any previous year, and the numbers for 3 of the previous 4 years were remarkably consistent in the mid-80s. We’ll leave the question of “statistical significance” for the next section (sort of), but for now, just ask yourself: Is that an impressive drop? A meaningful one? I don’t know. I’m less impressed than I was just looking at the 2015-2016 comparison considering there were only 6 fewer concussions in 2016 than 2013. Maybe 71 is within expected random historical variation and not indicative of a sustained or trending drop; maybe it’s an impressive 15% drop from 2012 and 2014-15. I’m not sure (you’ll read that a lot here).

If we stratify by concussions in games versus practices, things become a bit more interesting. Let’s start with practice concussions, which actually look substantially lower the last couple of years. Jeff Miller, the NFL’s senior vice president of health and safety policy, said “…it is a trend, we think, now after a couple of years that there are fewer concussions in practice.” OK, two sustained years of a 25% reduction in practice concussions is kind of compelling (though calling 29 to 26 from 2015-16 a “drop,” as John Clayton does here, is a stretch).

The game numbers are where I would have a problem with interpreting 2016’s preseason concussion figures as a drop. Look at those numbers; 45 concussions in 2016 is a 16% drop from 2015 (54), but it’s basically in line with the numbers from 2012-2014. Is that something to trumpet? Looking at those numbers, I’d say you could at best say that preseason game concussions are basically flat, with 2015 as a high outlier.

We can see the historical variation in these numbers, which we should expect a good bit of given, as Miller correctly points out, we’re dealing with a fairly small sample of concussions each preseason. Now let’s try and quantify how much variation we should be expecting…

Statistical Approach: Confidence Intervals

Skip to the end of this section if you don’t like statistical details. But I’m going to try and make this very accessible regardless of your math background, so stick around if you want to learn something!

We saw 71 concussions in the 2016 preseason, but that number is subject to something called random error that can cause the number of concussions to bounce around from year-to-year, even if the underlying rate of concussion (the thing the NFL has power over) isn’t changing!2 Quantifying how much might we expect these numbers to bounce around year to year can help us figure out whether 6 or 12 or 30 fewer concussions is actually a meaningful drop or not. So let’s get on that.

Coinflips and Concussions

The number of concussions we observe in a preseason is what we call a random variable. The statistical definition of this is quite dense, but what it boils to is it’s a number that we observed that could have been another number. Think of it like this. Take a coin out of your pocket. Flip it 10 times. How many heads did you observe? Let’s say you observed 5 heads, the most likely outcome for a fair coin. But you could have observed 6 or 8 or 1 by random chance - you just happened to observe 5. Flip it 10 more times and see if you get a different number of heads. The number of heads in 10 flips is a random variable!

The number of concussions we saw in the 2016 preseason can also be described as a random variable. Think of each player in a single game or practice as a coin flip. How many flips did we have in the 2016 preseason? Let’s assume each team has 90 players in each of the first 3 preseason games and 75 in the last one due to roster cutdowns. Then you have ((90*3+75)*32) = 11,040 “player-games” in the preseason. Let’s also assume each team has 6 weeks of 5 practices per week, with the first 5 weeks featuring 90 players and the last week featuring 75 players. Then you have (90*5*5*32)+(75*5*1*32) = 84,000 “player-practices.” Sum these two together, and we get 95,040 “athlete-exposures” (AEs), which is one athlete participating in one game or practice. This is equivalent to 95,040 flips of a coin which, if it comes up heads, means a concussion (thank you, I’m here all week).

Fortunately for us, this is not a “fair” coin, but a coin weighted heavily against coming up heads, as demonstrated by the fact that we only saw 71/95,040 flips come up heads (concussion). In fact, we can infer that the most likely value for the probability of heads on this unfair coin is 71/95,040 = 0.0007. If we flip a coin so weighted 95,040 times, we are most likely to see 71 heads/concussions. But we might have seen 68, or 83, or 129 by simple random chance.

Binomial Distribution

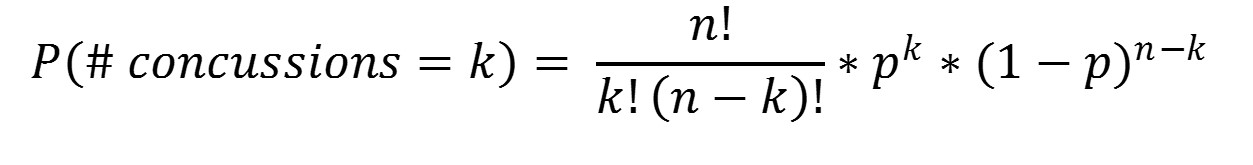

But exactly how likely are each of these other values? Random variables such as the number of preseason concussions - where you have k “successess” (concussions) in n “trials” (athlete-exposures) - are described by a mathematical function known as the binomial distribution:

Don’t get stuck on the equation. It just describes the probability of observing k concussions in n athlete-exposures where p is the proportion of athlete-exposures that result in a concussion (i.e. the probability of heads on our weighted coin). In 2016, our best guess for p is our observed proportion, or 71/95,040 = 0.0007.3 k can range from 0 to n concussions.

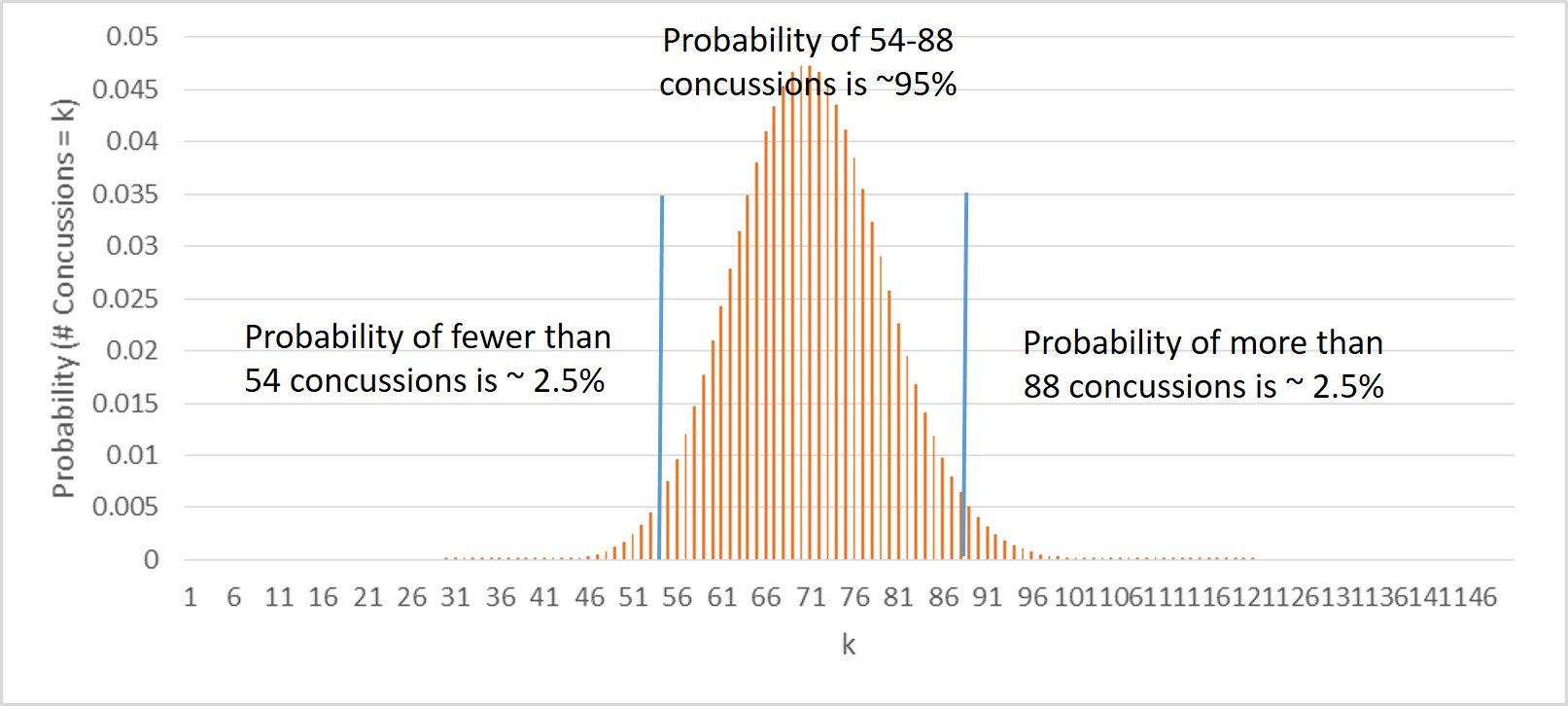

The probability will be largest for k = 71 and will grow progressively smaller the further away you move on either side. The exact figures are plotted below (with k truncated at 150 because observing more concussions than that is so vanishingly unlikely):

Confidence Interval

A common way to define a plausible range of values for any quantity is a 95% confidence interval. In our case, we’ll construct an exact binomial 95% confidence interval for the number of preseason concussions.

To do this, we need to take the binomial distribution from above and figure out the range of values around our observed value of 71 that sum up to 95% of the total probability. We do this by first finding a “lower bound” for the interval below 71, and then an “upper bound” for the interval above 71. The process is illustrated on the graph above.

For the lower bound, we start summing up the probability that we observed 0 concussions, then 1 concussion, then 2 concussions, and up and up and up until we reach a total of 2.5% probability. Why 2.5%? Well, we need 5% total probability outside our interval, so we want 2.5% on the low end and 2.5% on the high end. It turns out we reach 2.5% probability somewhere between 54 and 55 concussions - let’s say 54 to be safe.

For the upper bound, we start summing up the probability that we observed 95,040 concussions, then 95,039, then 95,038, and down and down and down until we reach a total of 2.5% probability. It turns out we reach 2.5% probability way down around between 87 and 88 concussions - let’s say 88 to be safe.

So, we can say for the 2016 preseason we observed 71 concussions with a 95% confidence interval of 54-88 concussions. One proper interpretation of this is that if the “true” or “mean” number of concussions in the 2016 preseason was 71 (which it might not be because of random error from our finite sample!), then if we repeated the 2016 season a zillion times we would observe between 54 and 88 concussions 95% of the time.4

A Plausible Range for Our Concussion Numbers

After incorporating random error to account for the fact that we only observed a finite number of concussions, games, and practices, we get the following numbers and 95% confidence intervals for the total preseason concussion numbers (all numbers rounded to nearest concussion). I could’ve done it for the game and practice numbers, but this post is so long already:

2012: 85 (67-103) 2013: 77 (59-95) 2014: 83 (65-101) 2015: 83 (65-101) 2016: 71 (54-88)5

All of these numbers are contained within each other’s 95% confidence intervals, suggesting that maybe we could have expected 71 concussions this year due to random chance rather than a true change in the underlying concussion rate.6 7

Conclusions

Taking into account our confidence intervals and the observed historical variation in concussion numbers, I’m not convinced 83 to 71 is a meaningful drop. There’s a decent shot we just observed a bit of a low outlier year due to random chance without any change in the underlying concussion rate – which is what the NFL can change and what it should be concerned about. However, I’m not totally convinced it’s not a meaningful drop, either! If I saw preseason concussions stay steady or continue to drop in 2017, I’d be more convinced. But even that might not be enough.

The regular season numbers offer another instructive tale about the difficulty of figuring out whether there’s a true trend in concussion frequency or not:

2012: 173 (95% confidence interval: 147-199) 2013: 148 (124-172) 2014: 115 (94-136) 2015: 183 (156-210)

The NFL looked like it was on the right track from 2012-2014 with two consecutive large decreases before concussions spiked again in 2015. Was that a real downward trend in 2013-14 or were they (especially 2014) just low outlier years? Was 2015 a high outlier year, or did that spike reflect some new true spike in the underlying concussion rate? It’s so hard to know, and we need to acknowledge that uncertainty rather than just comparing the numbers from two years to see whether they went up or down.

Footnotes

Keep in mind these are diagnosed or reported concussions. These numbers are therefore sensitive not only to changes in the “true” concussion rate and random variation but also to any changes in reporting practices or tendencies such as tweaks to the League’s concussion protocol.↩︎

Random error comes from the fact that we’re only looking at a finite sample of games, practices, and concussions. Some might argue that because we observed the entire NFL preseason in 2016, there is no random error in our measurement – we got the “true” number of concussions in the 2016 preseason, period. It’s a statistical philosophy debate with points on both sides, but I think about it like this: you know more about a QB’s true performance after 160 games than after 16 games than after 1 game, right? It doesn’t matter whether you’ve observed 100% of his games-to-date or not. There’s still random error from observing a finite sample of games regardless of the proportion that you measured, and that uncertainty needs to be accounted for! I feel more confident in my assessment of well-known fancy dog Tom Brady than I do Dak Prescott even though I’ve observed 100% of each of their games. I know more about Brady than I do about Dak and I need a way to quantify that lower uncertainty.↩︎

If we had some other outside information that p was actually a different value, such as 0.0001 or 0.1, we could then calculate the probability that we observed 71 concussions under those conditions. But here we’re assuming the true p is our observed proportion. You’ll see why shortly.↩︎

A very common misconception is the 95% confidence interval means you are 95% confident the “true” value lies somewhere in your interval. Technically, the correct interpretation is that if you measured your desired value over and over and over again and calculated 95% confidence intervals in the same way each time, 95% of those intervals would contain the “true” value you’re seeking to measure. An alternate interpretation – the one I used above – is that if you assume you have the “true” number of concussions, then you can say that in 95% of replications you would get a number within the 95% confidence interval (absent any other source of error or bias).↩︎

For the real stat nerds, I also tried treating concussion numbers as a count variable and constructed exact Poisson confidence intervals. They barely changed (shifted up by 1-2 concussions). Just wanted to cut that comment off at the knees. J/k nobody’s going to read this blog, I won’t get any comments.↩︎

For those who really want to know, the 2015 and 2016 numbers are not statistically significantly different at p=0.05. Hypothesis testing and p-values are the devil’s mathematics for many reasons I might expound upon in another post. You should always focus on proper estimation and uncertainty assessments, such as confidence intervals, rather than whether you get a p-value above or below an arbitrary threshold.↩︎

Keep in mind that these confidence intervals only account for random error. They do not account for additional uncertainty, such as whether concussion reporting or counting practices changed year-to-year, that could make our actual range of plausible values for each year even wider. Thus these intervals should be understood as the minimum uncertainty we have in these figures.↩︎