Is it Really Too Soon to Judge Roberto Aguayo?

I threatened to do this occasionally in my introductory post, but steel yourselves for a football analytics post that has nothing to do with injuries. You have ESPN’s Bill Barnwell and my friend and colleague Daniel Adler to blame for this.

On Bill’s December 5th show the two were discussing Roberto Aguayo, the kicker for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers that the team drafted in the 2nd round this year. Due to his high draft position Aguayo’s struggles – he is currently just 15/22 on field goals in the NFL – have been highly publicized. I’m heavily paraphrasing, but they basically came to the conclusion that it’s obviously far too soon to judge whether Roberto Aguayo is, in fact, a good, bad, or mediocre kicker.

Now Bill and Daniel are super smart guys, but I wondered if the statistics would bear them out…

Aguayo is currently 15/22 on field goal attempts, making him a 68.2% kicker overall. One (overly) simple way to estimate how good or bad he really is would be to basically treat each of Aguayo’s kicks as a weighted coinflip and see what range of weights (made field goals) could reasonably yield a 68.2% success rate. This is close to what I did with preseason concussion numbers in a previous post.

However, this approach presents a number of problems. First of all, every attempt is not created equal. The most obvious driver of field goal success is distance, so we need to account for that.

Second, this approach would put Aguayo in a vacuum and ignore everything we know from NFL history about true kicker success rates. It doesn’t make sense to say a priori that every possible field goal percentage is equally likely. We should find some way to incorporate that prior knowledge.

Third, it may be naiive – particularly in a case like Aguayo’s – to treat each field goal like an independent coin flip. The poor guy has been pilloried for every single miss…you’ve got to imagine that has some sort of compounding psychological effect making another miss more likely. On the other side, Justin Tucker is feelin’ it this year, so every successful kick might be making his next kicks more likely.

The approach I take below corrects for the first two issues. I’ll also explain the likely effects of the third (independence) issue.

Our Data

I scraped individual field goal data from 2011 through 2016 from Pro-Football-Reference using pages like this one. I only did the last 5 years because we know kickers have gotten better over time and I wanted an apples-to-apples comparison.

After excluding anybody with fewer than 20 attempts over this time period, we were left with 53 kickers including Aguayo.

Bayesian Analysis

I took a Bayesian approach to our question of whether it’s too soon to judge Aguayo. To provide a conceptual Bayesian introduction I’m going to shamelessly steal from Nate Silver’s The Signal and the Noise.

The Cheating Spouse Example

Say you want to estimate the chance of your partner cheating on you. You probably have some thought about how likely that is right now; in Bayesian terms, this is your “prior.” Fortunately for me, I love my wife (hi Amy!) and my prior for her cheating is extremely low, but not zero because if it were zero this example wouldn’t work.

But now let’s say I come home after a hard day at the blog mines and in the bedroom I find a pair of underwear that very clearly aren’t mine. This is some new “data” or “evidence” that I now need to incorporate into how likely it is that my wife is cheating on me.

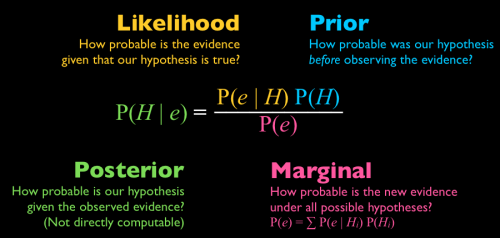

I could do that by the following: I take my “prior” probability of my wife cheating on me, multiply it by how much more likely it is for me to find the underwear if my wife is cheating on me than it is to just find the random underwear, and voila! I now have a “posterior” probability for how likely it is my wife is cheating on me given that I found the underwear. This is basically how humans reason, though not quite as explicitly or mathematically. The basic process is illustrated below:

Cheating Spouses and Roberty Aguayo

Now let’s apply this example to Aguayo. I want to estimate Aguayo’s true field goal “skill”. Before this season started I had the past 5 years of NFL data on kicker success rates – this is one reasonable “prior” for Aguayo’s skill.

Ah, but now I have some data (underwear) on how Aguayo has actually done. I can combine this data with our prior for his skill to get a new posterior estimate of Aguayo’s skill!

Our Prior

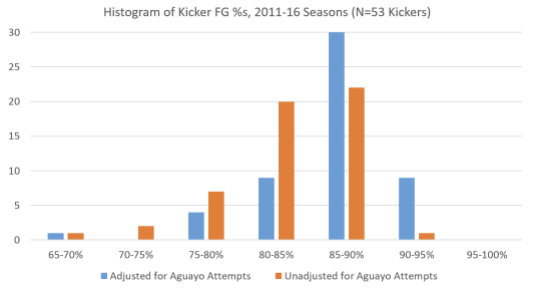

The first thing I looked at was the distribution of overall field goal percentages for 53 kickers with 20 or more kicks from 2011 through now. That’s the orange bars in the figure below:

However, first we need to adjust for the fact that Aguayo has actually faced an easier set of kicks than the average kicker. Only 1 of his 22 attempts has come from 50 or more yards away, with 14 of them from under 40. The blue bars are a weighted average of what each of the other 52 kickers’ percentages would have been had they had the same 0-39, 40-49, and 50+ yard distribution as Aguayo’s.

By the way, that blue bar over there on the left by his lonesome, 10% lower than anyone else? Sadly, Aguayo. The bad news is…that’s historically bad. The good news is it’s unlikely to continue to be that bad unless he’s in an unbeatable mental funk of some kind.

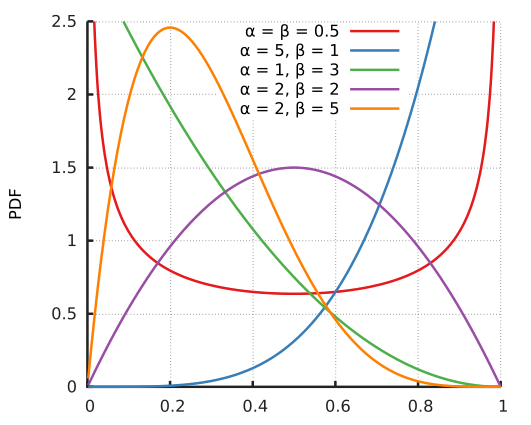

This distribution doesn’t look quite binomial (notice there was no one with an adjusted field goal percent below 65%), so we’re going to use a slightly fancier distribution to describe kicker success percentages: the beta distribution. The beta distribution is useful for a couple reasons.

First, it’s super flexible – by just varying a couple of numbers that define the curve (alpha and beta), you can get a whole lot of different shapes (see the figure on the right). The orange curve looks kinda like what we want, except we want it on the right and not on the left.

Second, it’s super easy to incorporate new information to get a posterior distribution. I’ll spare you all the math, but if we take our prior – which it turns out is best defined by alpha = 69.3 and beta = 10.6 – our posterior estimate is also a beta distribution with alpha = 69.3 + 15 Aguayo makes and beta = 10.6 + 7 Aguayo misses so far. Pretty badass, huh?

So…is Roberto Aguayo Bad or Not?

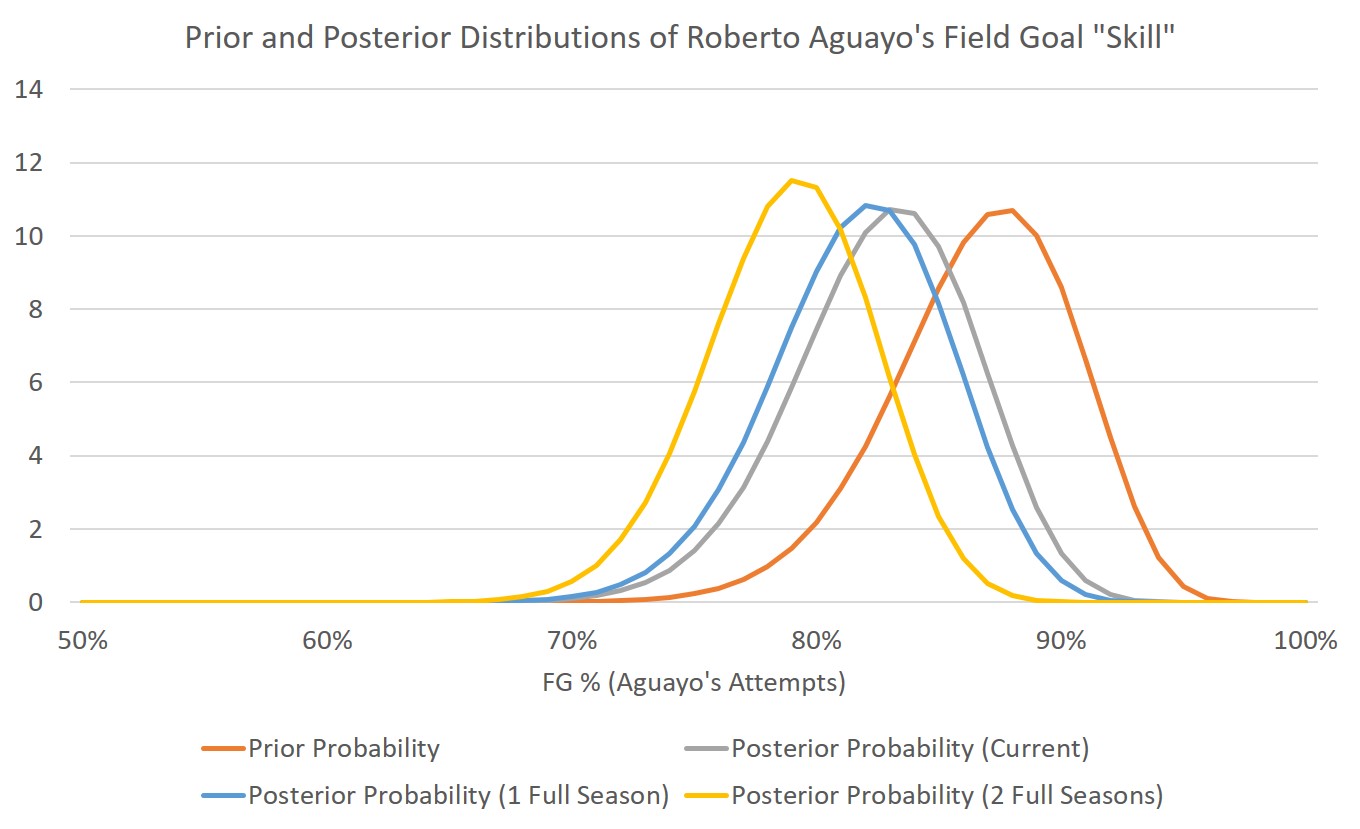

Here are our prior and posterior estimates for what Roberto Aguayo’s “true” field goal percentage is on a set of kicks similar to the ones he has attempted so far. Importantly, this is not an estimate of what his field goal percentage will be moving forward because he could make very different kicks! (NOTE: This chart and the numbers below were updated roughly 3 hours after the original post due to a coding error I discovered, but the main thrust of the results is unchanged.)

The orange line is our prior; this represents our best estimate of Aguayo’s skill on kicks of the type he’s taken before he ever takes a kick in the NFL. The higher the line is, the more likely that the value on the x-axis is his “true” skill.

The gray line incorporates the 22 kicks we’ve seen from him in 12 games so far. The blue line is what our estimate of his skill would be if we saw 4 more games of exactly the kind of kicks and makes/misses he’s had so far – I just multiplied the number of kicks so far by 4/3. The yellow line is the gray line, but after 2 full seasons.

Here are our means and credible intervals (similar to confidence intervals, but with a different interpretation and philosophy) for all distributions:

| Guess Type | “Best Guess” | 95% Credible Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |

| Prior (No Aguayo Kicks) | 87.6% | 78.5% |

| Posterior, Current Aguayo Kicks | 83.4% | 74.8% |

| Posterior, Full Season of Aguayo Kicks | 82.3% | 74.0% |

| Posterior, 2 Full Seasons of Aguayo Kicks | 79.3% | 71.7% |

Basically, before the season started our best guess is on 22 kicks of this type Aguayo would’ve nailed 87.6% of them if he’s basically like the group of kickers we included in our prior (everybody with >20 kicks from 2011-now). Instead, he’s made 68.2% of these kicks – poor kid.

If we consider that we’ve only seen 22 of his kicks and have data on 5,653 other kicks since 2011, our best guess for how he does in the future onthese types of kicks is 83.4%. Not as bad as he is now, but that still only puts him better than about 20-25% of NFL kickers. Yikes. Still, there’s a decent chance his skill turns out to be better than that – there’s a 95% chance his true skill on these kicks is between 74.0% and 89.4%. 89.4% would put him in the top fifth or so.

If we continue to see this same kind of performance from Aguayo through the rest of the year, our best guess for how he does in the future would drop to 82.3%. After another full season on top of that, 79.3%, with only a small chance that he’s truly even a League-average kicker. This is an example of the “data swamping the prior” – we put progressively more and more weight on what Aguayo actually does as he, well, does more and more of it.

Conclusions and Limitations

I don’t yet disagree with Bill and Daniel that it’s too early to tell, but it’s not looking good. The information Aguayo has given us so far already suggests he’s more likely to be a below-average kicker than not, driven especially by how comparably easy his kicks so far have been. On the plus side, though, it’s not likely he continues to be this bad, either. If we see this performance continue through a second season we will pretty much be able to say he’s a bad NFL kicker.

However, our analysis may be unduly cruel to Aguayo for a couple reasons. First, we used the information from all NFL kickers from 2011-2016 to create our prior. Aguayo – drafted in the second round – was supposed to be better than most kickers. If we’d used a prior distribution of just the top 20 or 30% of kickers – which may have been more appropriate – his posteriors would also look better now. Second, Jesus, the guy’s just had a rough year, and our model doesn’t account for the non-independence of his kicks (i.e. the compounding effects of pressure and missing kick after kick). If he can get out of any nasty mental spiral his percentage could increase a lot more than our model anticipates. That would be great! I’m certainly rooting for that.

One other limitation worth noting is the prior is only built on kickers who “survived” to make 20 NFL kicks. So we’re not including the possibility that Aguayo is actually bad enough to have never made it this far without having been drafted in the second round – something Bill and Daniel pointed out on the podcast.

So our analysis isn’t looking great for Aguayo, but it also represents a pretty pessimistic estimate of his future chances.